“Laborem exercens” and “The Spirit of Human Work” by Stefan Wyszyński

Few people remember today that Stefan Wyszyński was one of the pioneers of contemporary theological considerations concerning work. At the turn of 1950s and 1960s, his most important work in this field, The Spirit of Human Work - was translated into Spanish, German, Portuguese, French, English, Dutch and Italian. On the 40th anniversary of the “Laborem exercens” encyclical, it is worth considering the extent to which this reflection shaped understanding of work by John Paul II.

Cardinals Stefan Wyszyński and Karol Wojtyła during the procession to Skałka in 1976. Photo. Stanisław Składanowski

Drag timeline

1946

First edition of “The Spirit of Human Work” by Stefan Wyszyński. Priest Stefan Wyszyński had already been nominated as Bishop of Lublin, Karol Wojtyla was completing his theological studies in Kraków at that time.

1957-1961

Subsequent editions of “The Spirit of Human Work” are published. In 1957, it is reissued in Poland (it was later banned from print by the communist authorities). 8 foreign editions are published at the turn of 1950s and 1960s. In this period, Priest Karol Wojtyla was appointed as the Auxiliary Bishop of Kraków and his direct cooperation with Primate Stefan Wyszyński began.

1981

The publication of the “Laborem exercens” encyclical scheduled for 15 May 1981, is postponed due to the assassination attempt on the Pope. Two weeks later, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński dies. Ultimately, “Laborem exercens” is not issued until 14 September 1981.

Shared vision

The "Laborem exercens" encyclical was to be published on 15 May 1981. By then the Primate was already dying, suffering from pancreatic cancer. He had not left his bed since the end of March, but remained in contact with John Paul II. To the very end of his life, the fate of Polish workers remained the Primate's main concern. On 28 March, in one of his last letters to the Primate, the Pope wrote about Poles “who see the need to commit themselves fully to their work”.

On 13 May the world was shocked by the news of the assassination attempt on John Paul II. The Pope was taken to hospital in a critical condition. The publication of the encyclical was out of the question. Stefan Wyszyński died two weeks later. He did not have enough time to learn about the papal encyclical on the subject he considered one of the most important in his pastoral work and which was his greatest scholarly passion. “Laborem exercens” was not issued until 14 September 1981.

“The Spirit of Human Work” was published by Wyszyński in 1946, while he was still a priest. The book was written during the Second World War - he included in it the conference speeches he delivered during secret lessons in Warsaw and in Laski. Thirty-five years separate this book from ”Laborem exercens”, a period during which the circumstances of work had changed profoundly. Wyszyński's book was supposed to provide strength to rebuild the country after the war. “Laborem exercens” was written “when the ‘global’ problem came to the fore”, i.e. the “disproportionate distribution of wealth and misery” in different regions of the world. The encyclical admonished the "dignity and rights of working people" worldwide.

The just fight

“Laborem exercens” is to a certain extent a call to fight “for the legitimate rights of working people”. In the encyclical, John Paul II confronted himself with the idea of class struggle, the struggle of workers against employers. He wrote that it had erupted on a large scale primarily through the political activities of the communists, but he saw the real conflict as its source: the owners of the means of production often exploited their advantage over the workers by failing to provide them with adequate working conditions. Genuine conflict of interest and manifest injustice have a right to lead to a fight. “It should be regarded as a usual endeavour for the right good (...), rather than a struggle 'against' others. (...) Work, above all, brings people together”.

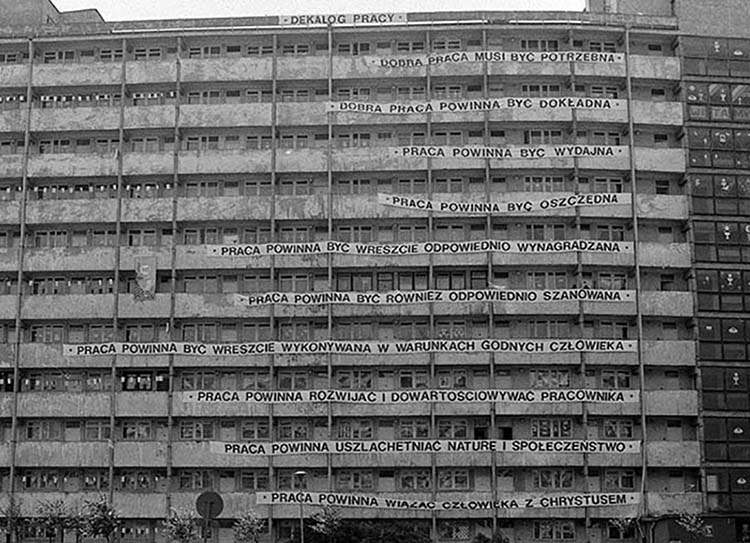

Banners on an apartment block during the pilgrimage of John Paul II to Poland in 1987. Photo. Stanisław Składanowski

The feature of a man

Man is predestined to work, John Paul II wrote at the beginning of the encyclical, “only man is capable of doing work and only man does it”. “Work bears the particular feature of man”, the feature fundamental for his very nature. Stefan Wyszyński’s reasoning was similar: “In fact, there is no work in the strict sense of this word that can be disconnected from man”.

Work is thus an expression of human nature, and its purpose is also a man himself: “The myth of payment for work won in all of us: a day's pay, a piecework, a salary, a fee,” Priest Wyszyński wrote. On the other hand, work should include the improvement of the working man as its primary goal: “it should be performed in such a way that, as a result of it, man becomes better, not only in the sense of physical fitness, but also in the sense of moral values”. Thus, although different jobs may have different values in terms of the type of activity performed (the work of a doctor may certainly be valued more highly than that of a journalist), since work is always performed by man for man, the value of work “is measured above all by the dignity of the very subject of the work (...), the man who performs it”.

Participation

The employer's duty in this perspective is to create a workplace where the employee will develop not only professional skills but also soft competence and where each employee will be in a sense the host, where he/she will feel that they work “on their own”. In fact, one cannot be achieved without the other. Comprehensive development is only possible with the involvement of the whole person in the work, i.e. “mind, will, feeling, physical strength”, as Priest Wyszyński writes. This cannot be done without at least a minimum involvement of workers in the decision-making process. On the other hand, employees who are constantly acquiring new competence, can become increasingly involved in the management of the company.

In “Laborem exercens”, John Paul II showed two specific ways in which workers can influence the workplace. The first is the trade union activity. The Pope would only want unions to engage in the struggle against employers as a last resort, e.g. through strikes. Ultimately, as John Paul II wrote, in a community of work “both those who work and those who dispose of the means of production must join forces”. Trade unions should therefore act in the greatest possible harmony with employers.

The second way of changing workers into hosts mentioned by John Paul II is the idea of including workers in the shares or profits of the company in which they work. John Paul II referred to a principle that has been repeated in the Catholic Church since the time of Saint Thomas Aquinas: the right to ownership is subordinate to the right to the common use of goods. According to this teaching, material means cannot be possessed for the sake of possessing. When referring to this principle, Priest Wyszyński writes about the necessity of giving the money one earns beyond one's own needs to those in need. John Paul II further developed his conclusions, deriving from this the legitimacy of workers' share in the profits or shares of a company.

Source of dignity

All the “external work” - as Priest Wyszyński called it - or the “subject work” - as John Paul II wrote about it, has its source in the subjectivity of work. Changing the outside world is properly implemented when human subjectivity is respected at work. Priest Wyszyński formulated the principle stating that “the inner life is the basis of the outer life” - personal development in the sense of, e.g., the development of virtues is necessary to achieve the appropriate effects of work, as indicated by the Pope and the future Primate: the development of science and technology, building of culture, multiplication of welfare in the nation and through the nation - of universal welfare, the development of justice and fraternity.

For both authors, external work is of momentous importance - it completes God's creation of the world. “Man, created in the image of the God, by his work participates in the work of his Creator - and, to the extent of his human capacities, in a certain sense further develops and completes it,” the Pope wrote. The future Primate perceived it the same way: “[The God] entrusts the execution of his plan in detail to man”.

Primate Wyszyński was famous for his very intense work. Photo Maria Okońska/Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński Primate Institute

“For created in the image and likeness of the God Himself in the midst of the visible universe, instituted to make the earth subject to Himself, man is by the same calling from the beginning to work”. This is how both authors understand the God's blessing addressed to man as recorded in the Genesis: “Make the Earth subordinated to yourselves”. Man's work expresses his likeness to the God-creator whose work of creating the world is depicted in the Bible as work. In his work, man also becomes like Jesus who as a carpenter “devoted several years of his life to manual labour”. Both argued that in the toil of work “united with the Christ crucified for us, man cooperates in a certain way with the Son of God in the redemption of mankind”.Although John Paul II addressed his encyclical not only to Christians but to all people of good will, it must be noted that the dignity of human work in the Pope's work is based - as in the work of the future Primate - exclusively on Christian revelation. For those who do not recognise the Bible as divine revelation, the encyclical lacks an acceptable justification for the dignity of human work

Inspiration

“Laborem exercens” and “The Spirit of Human Work” discuss work in a coherent way. This is certainly largely due to the fact that John Paul II and Stefan Wyszyński were formed in the same tradition of thought. The common points of reference are, therefore, first and foremost the Bible, the works of St. Thomas Aquinas and the encyclicals of earlier popes concerning the Catholic social teaching. Both works were also written in the context of the two economic doctrines competing in the world at the time: liberalism and communism.

Quotes about work - comparison

John Paul II about work – quotes from “Laborem exercens”

- “Work bears a particular mark of man and of humanity, the mark of a person operating within a community of persons. And this mark decides its interior characteristics; in a sense it constitutes its very nature”.

- “[H]uman work is a key, probably the essential key, to the whole social question, if we try to see that question really from the point of view of man's good”. “In fact there is no doubt that human work has an ethical value of its own, which clearly and directly remain linked to the fact that the one who carries it out is a person, a conscious and free subject, that is to say a subject that decides about himself”.

- “[T]he primary basis of the value of work is man himself, who is its subject. This leads immediately to a very important conclusion of an ethical nature: however true it may be that man is destined for work and called to it, in the first place work is ‘for man’ and not man ‘for work’”.

- “A man [...] ought to be treated as the effective subject of work and its [production] true maker and creator”.

- “The word of God's revelation is profoundly marked by the fundamental truth that man, created in the image of God, shares by his work in the activity of the Creator and that, within the limits of his own human capabilities, man in a sense continues to develop that activity, and perfects it as he advances further and further in the discovery of the resources and values contained in the whole of creation”.

Stefan Wyszyński about work – quotes from “The Spirit of Human Work”

- “For work is strongly linked to the human will. In fact, there is no work in the strict sense of this word that can be disconnected from man”.

- “Work connects man to man - there is no doubt about that. There is no such work in which a person would be exclusively confined”.

- “Our mind, will, feeling, physical force take part in it. We have the ideal image of the working man precisely when none of the gifts that man has received is excluded from participation in the course of work”.

- “Work is not so much a sad necessity, not only a rescue from hunger and cold, but it is a need of the rational nature of man who comes to know himself fully and expresses himself completely through work”.

- “When we become immersed in the Divine intentions, when we cooperate with Him, the hardest work loses some of its weight (...). The work acquires nobility, sublimity and dignity. Even the dirtiest work becomes a service for the God. The God did not diminish His glory by lowering Himself to the muck of the earth when He brought Adam out of it. The lowest work contains the stigma of humanity and sonship of God”.

Author of the text: Ignacy Masny

The Centre for the Thought of John Paul II

Sources

Video Records

Documents

Video Records

Event Place

Choose location...

Włocławek

Vatican

Keywords

Persons index:

Project implemented by:

Project co-financed by:

Patronage:

Partners: