John Paul II's pilgrimages to Poland were mass events, exceptional in terms of the number of participants and the difficulty of preparation. It was no different in 1987. For six days, from 8 to 13 June, the Pope visited nine cities. An intensive programme was planned in each of the cities and the central events gathered hundreds of thousands of people. According to

the survey conducted by the Public Opinion Research Centre (OBOP), one third of Poles wanted to take part directly in the meetings with the Pope, i.e. more than 13 million people. Only 3 per cent of respondents expressed no interest in the pilgrimage. This means that more than 30 million Poles followed the teaching of John Paul II with more or less attention.

1. Love

"In the visible world there is one subject, one hotspot (...). Man is such a hotspot," the Pope said in his homily on the last day of his pilgrimage. He began his pilgrimage

at Warsaw Okęcie airport with his humanist credo – “every man is the way of the Church”. The speech left no doubt that John Paul II's main goals were religious and that he wanted to base all social transformations on the spiritual transformation of individuals. He spoke primarily about the sacrament of the Eucharist in the context of the Second National Eucharistic Congress which was about to begin. The Pope's visit was part of this event - he began with Mass on the first day of his pilgrimage in Warsaw and ended with Mass and a solemn procession with the Blessed Sacrament also in the capital. Other cities on the pilgrimage route were the stations of the Congress, during which, in addition to celebrations with the Holy Father, other events were held to strengthen the Eucharistic devotion, including nightly Eucharistic adoration.

This sacrament, John Paul II said, builds community. In the Eucharist, "the sacrament of man's love for man", he saw the true source of solidarity. This was most fully presented by the Holy Father in his

homily at the end of the Eucharistic Congress at the Defilad Square in Warsaw. The proper basis of solidarity and every community is love. Man is obliged to love, but at the same time proves incapable of it. Only Jesus, as God incarnate, was the first man capable of fulfilling the call "Thou shalt love". According to John Paul II, it is only the Eucharist, in which Jesus gives himself to man, that makes it possible to respond "with love to Love". And "one can only love oneself, one's neighbour and the world by loving God".

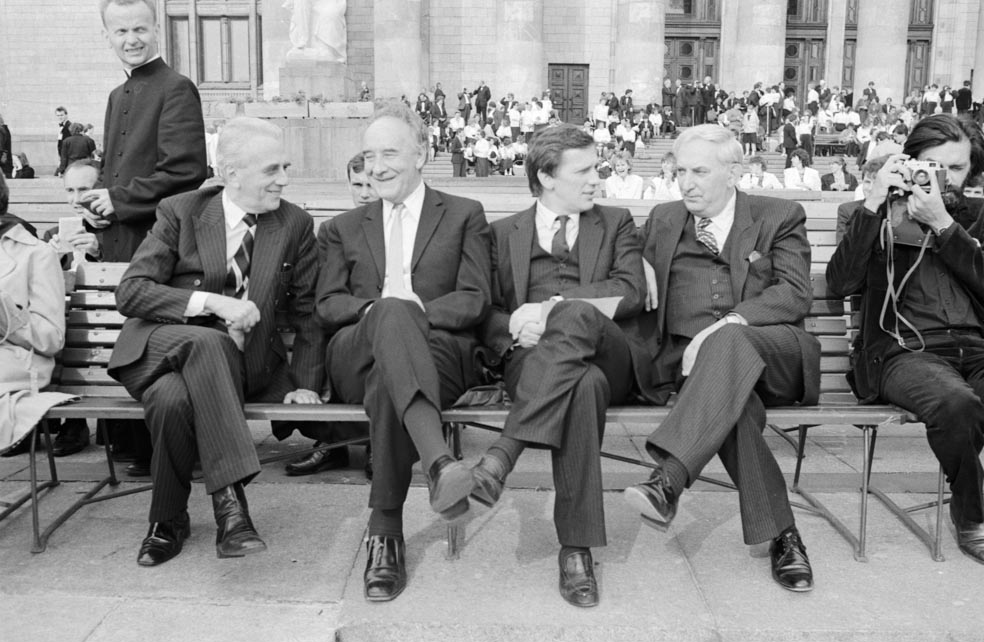

John Paul II, 14 June 1987. Photo by Stanisław Składanowski.

In this homily, the Pope unequivocally identified the Eucharist as the only solid foundation of any community. In an impromptu

address to young people from the window of the archbishop's palace in Kraków, he called it "the beginning of all solidarity". There he also called it the sacrament of "empowerment", indicating that it is in it that young people should seek their subjectivity - also in the social dimension.

2. Subjectivity

"Man is strong, strong with a consciousness of goals, a consciousness of tasks, a consciousness of duties" - this is how John Paul II explained to the young people of Kraków where true subjectivity comes from in man. He continued this theme in

his famous homily at Westerplatte, also to young people: "one speaks rightly of human rights. (...) We must not forget, however, that human rights are there to give everyone the space they need to fulfil their tasks and duties. (...) Human rights must be the basis of that moral power which man achieves through fidelity to truth and duty". This was a call to build inner subjectivity, which he referred to as the "moral power".

At the beginning of his pilgrimage, he reminded it to the authorities of the People's Republic of Poland and personally to Wojciech Jaruzelski.

On 8 June, at the Royal Castle in Warsaw he said: "Only then does a nation live authentically its own life when it asserts its subjectivity in the whole organisation of the state life. It states that it is the host in its home". With his teaching on subjectivity, he struck not only at the political practice of the communists, but also at the ideological basis of their power. Contradicting Marxism, which proclaims that historical processes are determined by social relations, John Paul II said

to the Polish episcopate: man "above all is a person, he is the subject of his actions. The subject of morality. The subject of history".

Subsequent speeches to various circles, in which the call for subjectivity or sovereignty is repeated like a refrain, should be understood in this context.

To the scientific community, the Pope said: "This subjectivity is worked out everywhere, at the various workplaces on this native land of ours. There are industrial and agricultural work environments called to it. There is the family and every individual called to it. Subjectivity arises from the very nature of personal being: it corresponds in the first place to the dignity of the human person." To all these circles: the farmers at a mass for more than 2 million people

in Tarnow and the workers in Gdańsk, the families in Szczecin,

the children in Łódź,

the priests in Lublin and

the cloistered sisters in Warsaw - he reminded them all of their personal duty to act freely and sovereignly for the good of the whole community. But also that it is the human right for the state to provide the conditions for such activity.

3. Solidarity

The Pope's statements about subjectivity struck directly at the state authorities. It was clear to everyone that, in Polish conditions, the attempt at such subjectivity was primarily made by the Solidarity trade union, whose activity was brutally suppressed by those in power. When the Pope said

to the representatives of the authorities in the Warsaw castle: "remember man. (...) about his right to religious freedom, to associate and to express his views", it was clear that he was reproaching the authorities for, among other things, imposing martial law, breaking social agreements and imprisoning almost all of Solidarity's most important activists. According to an OBOP survey, 70 per cent of Poles knew the content of this speech - perceived as anti-state both in party analyses and in foreign media. It is hardly surprising that the PRL authorities perceived the Pope's visit as a direct threat to the political system.

John Paul II did not hesitate to speak the truth about human rights violations by the communist regime. He also expressed support for Solidarity. Above all, his words "he wants to speak about you, and in a certain sense for you", with which he expressed solidarity with the workers at

Zaspa in Gdańsk and made it clear that they themselves could not speak out freely, have gone down in history. Equally important were gestures such as praying in front of the monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers 1970, commemorating the bloodily suppressed workers' revolt, or at the grave of the murdered Solidarity chaplain Fr Jerzy Popiełuszko. Popiełuszko, in fact, was mentioned by the Pope many times in homilies and speeches, as were the strikes and August Agreements of 1980 and the lesser-known agreements of the Solidarity agricultural organisations - in Rzeszów and Bydgoszcz.

The behaviour of the listening crowds also signalled that the meetings with the Pope had a political context in addition to the religious one. Shouts, applause, banners and opposition leaflets constantly created an atmosphere of confrontation. The Ministry of the Interior did a great deal of work to prevent such a pronouncement of the pilgrimage. An operation code-named "Zorza II" was launched for this purpose. It was to secure the pilgrimage in the context of the standard threats that accompany the arrival of important personalities and mass gatherings - and this in itself, due to the size of the event, posed an enormous challenge. The job was, incidentally, well appreciated by both the public and the Pope himself. At the same time, 'Aurora II' was intended to protect the state from activities directed against the communist system. The operation involved preventive arrests of some opposition activists, searches of their homes, and the requisitioning of Solidarity leaflets and banners. There was no shortage of bizarre actions either. In Gdańsk, at the monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers 1970, several thousand plainclothes officers of the Ministry of the Interior, PZPR activists and soldiers were lined up at the foot of the monument to the Holy Father, their backs turned. In this way, they were to show disrespect to the Pope paying tribute to the fallen and at the same time separate him from the crowd gathered there.

4. Other events

Gdańsk was the highlight of the pilgrimage, where John Paul II's call for subjectivity and support for Solidarity resonated most strongly. However, the main theme of the mass at Zaspa was work. John Paul II devoted a great deal of attention to it during his pilgrimage, trying to convey the Church's social teaching in simple words. "Work - it means man," he said, pointing out that work must not be treated as a commodity.

He also recalled proper working conditions: in Gdańsk, fair pay, and in Łódź, at

a meeting with fibre workers, the need to ensure proper conditions for women to combine work with their role as mothers. He recalled the Church's demand "that all that a woman does at home, all the activities of a mother and educator, be fully appreciated as work. This is great work". This was, according to many accounts, the most moving encounter of the pilgrimage, during which John Paul II spoke with deep emotion about his childhood years spent with his mother. He spoke with equal emotion at

a Mass for families in Szczecin, where he spoke of mass culture and its victims: "betrayed, abandoned and abandoned wives", "abandoned husbands", "spiritually crippled children".

Defilad Square in Warsaw during the papal pilgrimage. Visible on the photograph are Jan Englert and Gustaw Holoubek, among others. Photo: Stanisław Składanowski.