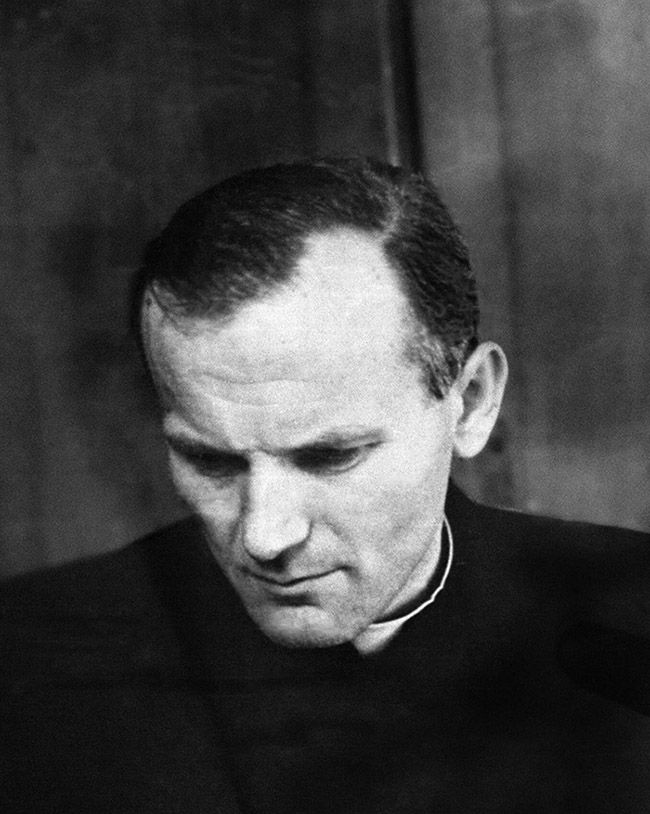

Karol Wojtyła and the Worker-Priests

18 May 1947

3 July 1947

July 1947

August 1947

September-October 1947

6 March 1949

A Gift from the Prince

In May 1947, Adam Sapieha, Prince and Archbishop of Krakow, visited the young priest Karol Wojtyła in Rome. Wojtyła lived at the Belgian College and was working on his PhD dissertation at the Angelicum in Rome. Sapieha decided to send him, together with his friend Stanisław Starowieyski, on a journey to France, Belgium, and Holland. They were to rest, get acquainted with the sacred art of the West, but above all — to learn new methods of pastoral work.

Wojtyła was already somewhat familiar with the workers’ environment. During the war, he spent four years working at the Solvay factory in Krakow. However, in Rome, he had the opportunity to get to know the subject from the theoretical side. There was an abundance of opportunities for discussion and reading about the labour movement at the Belgian College. It was the hottest topic when the Soviet Union controlled half of Europe, and Communist parties were reaching the peak of their popularity in Western countries. The issue of workers seemed to be one of the most pressing for the Church at the time.

They set off in July. As the Pope later wrote in his book “The Gift and the Mystery,” they began a journey of “immense importance”.

Meeting with the Dockworker

The first longer stop on their journey was Marseille. In a city with one of Europe’s largest ports, there are a lot of dockworkers. However, Karol Wojtyła and Stanisław Starowieyski were looking for a particular one — his name was Jacques Loew, and he was a Dominican. Fr Loew had already been working as a dockworker for six years. He became famous for a survey published in 1943 on the life of Marseilles port workers, in which he showed the misery and working conditions of his colleagues. When he met Wojtyła, he had already been a parish priest in La Cabucelle for a year.

Loew recalled how during lunch, one of the workers called priests “pigs who exploit others”. The priest worked there like everyone else, dressed in workers’ overalls, so the co-workers did not know who they were dealing with. “Do you know the priest from Cabucelle?” he asked. „No.” “That’s who I am,” Loew said and explained that he understood working on the docks as following Jesus — suffering alongside the poor. Worker-priests tried to live like fellow factory workers. They performed full-time work, often beyond their strength. Jacques Loew recalled that he could barely manage to carry registered parcels. Another priest-dockworker, Michel Favreau, died crushed by a ton of wood in the docks of Bordeaux.

Making such an effort for many priests proved to be a path to leaving the priesthood. Exhaustion often prevented them from fulfilling their priestly duties of prayer and daily Mass. Sharing the workers’ plight also often led to involvement in the class struggle, trade unions, and protests. In 1952, two priests were beaten up and arrested for taking part in a demonstration. Therefore, the experiment with worker-priests led to much tension and constant control over whether the participating priests forgot their spiritual ministry. It was even temporarily interrupted for this reason by Pope Pius XII. Some worker-priests then left their work for the Church in favour of the French Communist Party.

However, this was not the case for Loew. Like many other priests of the movement, he reconciled his work as a dockworker with his duties as a parish priest. Wojtyła described his work and that of other worker-priests he met during his holidays in his debut article in the “Tygodnik Powszechny” in 1949: “It is not an activity of resistance, opposition, an ’anti’ activity — on the contrary, it is a positive, constructive activity that seeks to build up. (...) it aims to produce a new type of Christian culture. And he builds it (...) in environments where sometimes even the traces of former buildings have disappeared.”

Priest or Bonza?

Jacques Loew was one of the informal leaders of the movement. Before the war, the first priests who decided to combine pastoral service with professional work in a factory had already been. During the Second World War, a sense of detachment from the realities of life for industrial workers grew in the French Church. Several hundred priests were sent to French forced labour in the Third Reich, where they discovered that Christian culture no longer existed among them: “My Latin, my liturgy, my theology, my Mass, my prayers, my priestly vestments — all this made me someone else to them, an interesting phenomenon, someone like an orthodox priest or a Japanese bonza,” recalled one of these priests. In 1943, the Archbishop of Paris founded a special seminary to prepare priests for work among workers. One part of the training was an internship in a factory. The following year, the first priests began working in the industrial enterprises of Paris.

The next stage of Karol Wojtyła’s journey was Paris. During his over two weeks there, he met the theoretician of the new movement, Rev. Georges Michonneau, author of the book “Parish — Missionary Community,” a report on his work in the far suburbs of Paris. Wojtyła visited him in his parish in Colombes, on the outskirts of the Paris metropolitan area. He saw priests who tried to make their lives similar to those of their parishioners. The principle was to live at a level slightly below the residents’ standard of living while completely waiving pastoral fees. The priests supported the parish with voluntary donations and lived off manual labour. “Working together overcomes hostile attitudes, unites with a common workshop, a certain community of life interests,” wrote Rev. Wojtyła in the “Tygodnik Powszechny”. He was attracted by the religious theme of working side by side with the parishioners, as pointed out by the worker-priests. During Mass, a priest offers a sacrifice on the altar, in which the whole effort of the believers is to be included. The priest’s direct participation in their daily grind can allow him to “connect this sacrifice in a more personal way with all that his environment can offer to the Heavenly Father.”

See, Evaluate, Act

Nine years earlier — in 1938 — 75,000 young workers in berets and uniforms had gathered at the Parc des Princes in Paris. They held torches and banners in their hands. As a journalist from the British magazine “Time” wrote, it would have been difficult to distinguish them from the Communist youth if it were not for the fact that they all knelt before the cross in the presence of the Archbishop. They were members of the Jeneusse ouvrière chrétienne (JOC; Fr. Young Christian Workers), a thriving Catholic workers’ organisation (around half a million members in Europe), who gathered to celebrate the movement’s anniversary.

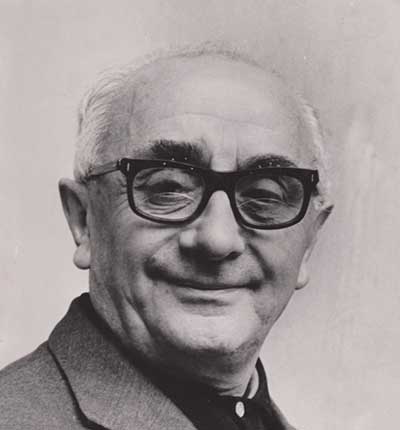

Rev. Karol Wojtyła left Paris at the beginning of August 1947 and came to Belgium to understand the activities of the JOC in the place where the organisation was founded — in Brussels, in the parish of Fr Joseph Cardijn, its founder. At the time, it seemed that the JOC was the Church’s best response to the secularisation of workers and the growing influence of Marxism among them. Worker-priests sometimes came from the JOC, but Cardijn himself was opposed to the movement. “A priest-worker can never be a real worker because at any moment he can stop being a worker,” he argued. In the JOC, priests were to perform pastoral assignments, and Cardijn wanted to leave the building of an equitable culture based on Catholic social teaching to the young members.

He believed that well-rounded young people were capable of changing the world around them. He recommended the “see — evaluate — act” method, whereby they would learn in small groups to look closely at the problems of others, analyse them together, and take action to restore justice.

Authentic Model of Activism

Wojtyła had the opportunity to meet the charismatic founder of the JOC in Rome, as Cardijn was a frequent visitor to the Belgian College. His views were often controversial because of his suspected Marxist sympathies. Indeed, Cardijn was intensely learning the work of Karl Marx when he was arrested for patriotic activities during the First World War. In 1919, he founded the Young Syndicalist Movement, with which he aroused the resistance of part of the Church, but soon more and more words of praise began to appear. “At last, someone comes to speak to me about the masses!” said Pope Pius XI of him and called his work an “authentic model” of social activism. After the war, he operated with the full approval of the Church. He contributed much to the content of the Second Vatican Council’s meeting. Shortly before he died in 1967, he was elevated to the dignity of Cardinal. His beatification process began in 2014.

Karol Wojtyła was greatly impressed by his work. In Brussels, he lived in premises belonging to the JOC and became closely acquainted with the organisation. In September, he moved to Charlerois, where he worked for a month as a priest for the Polish Catholic Mission in Belgium. He lived for a week among miners in Péronnes-lez-Binche. He tried to participate in their lives as much as possible, went down to the mines, accompanied a sick man whose health deteriorated because of working in a mine. For a month, he managed to get used to his temporary parishioners and, as Rev. Stanisław Starowieyski recalled, “was warmly welcomed by them”.

Evangelical Radicalism

The last stop on Wojtyła’s great journey was Ars, a small town near Lyon, where a century earlier, St John Mary Vianney, known for his total devotion to his parishioners, had been a parish priest. Many years later, in a conversation with André Frossard, John Paul II said: “If John Vianney had lived in our era, he would certainly have tried to transfer all the heroism of his priestly life, all that evangelical radicalism that beams from his figure to the context of the conditions of the contemporary apostolate and pastoral ministry. Can you think that he would have become a worker-priest? I think you can if you take into account that evangelical radicalism that is also contained in this concept of priestly life.”

It had been in 1982, and in 1985, at the tomb of Cardinal Joseph Cardijn in Brussels, John Paul II said: “What was most striking about Cardijn’s personality was his great love for the workers and their families. As a vicar here in Laeken, he brought together young male and female workers, gathered around him and gave courage to those people unable to get out of their demanding situation on their own.” When writing the Encyclical “Laborem exercens,” published in 1981, in which he took up the subject of human labour, John Paul II still had those experiences of his youth before his eyes. The work of the priests Jacques Loew, Georges Michonneau, and Joseph Cardijn, which he watched with admiration during the long summer holidays of 1947, sank deeply into his memory.

Laborem Exercens

Sources

Event Place

Keywords

Connected materials: